For the people of war-torn Mariinka, bread is a reminder of better days.

MARIINKA, Ukraine—

It’s a very small cup: blue dotted with yellow, the colors of the Ukrainian flag. But for Yelena, it holds a lot of history. It’s a reminder of almost thirty years’ labor, and of the day they ended in summer 2014, when an artillery shell landed on the bread factory where she’d worked all her life in Mariinka, east Ukraine.

Now, the cup sits on a table beside an Orthodox icon in Mariinka’s small, local bakery; a survivor of the on-going war in east Ukraine. “We went back [to the factory] after it was bombed,” Yelena tells me, “and I saw my cup there. I cried. And my little stool was still there… The icon too, our icon. We had a table in the workshop, like now, and it was above the table all the time.”

Yelena’s new workshop is in a former supermarket in Mariinka town center, a ‘gray zone’ in a conflict that’s claimed 10,000 lives since 2014. Reborn from staff and equipment of the destroyed factory, the non-profit bakery was opened in March 2016 by the Dobra Vest (Good News) evangelical church. It’s Ukraine’s first frontline workplace-generating enterprise, and a haven from the politics, propaganda, and violence that have torn Mariinka apart.

It’s late evening in the spring of 2017, although with no windows lining the bright, orange-painted walls it’s hard to tell the time, or hear the boom and rattle of artillery and machine-gun fire that starts up outside at 5 p.m., prompt as a curfew siren emptying the streets. Because of the shooting, workers stay all night at the bakery. It’s too dangerous to go home before morning.

The biscuit mixture is resting; the first batch of bread loaves is in the ovens. Yelena and fellow baker Olya work together with the speed and ease of long practice, making pizzas and buns that the bakery sells for just under market price in Mariinka and surrounding towns, or distributes for free to citizens deprived of work and income, gas and water, homes and family, by the war.

“We’re trying to make something tasty for people, because you see how we live here,” says Yelena. “If it ends one day—and God willing, every war has to end—well, then we’ll have to live further.”

More than three years after the July 2014 battle to take back Mariinka from armed Russian-backed separatists, the war between Ukraine’s government forces and its Russian-supported breakaway eastern region continues, and the frontline runs right through Mariinka.

Most of the town is back under government control. Donetsk, the urban center six miles away which locals once relied on for work, higher education, shopping, and entertainment, is capital of the unrecognized ‘Donetsk People’s Republic’ (DNR). The frontline runs northeast of Mariinka’s center, cutting across residential roads that lead to Donetsk. Many of the roadside houses, their windows regularly patched up and then broken again by explosions and gunfire, are still inhabited by locals who are unable or unwilling to move away. Yelena lives in one of them with her 29-year-old pregnant daughter Viktoria and granddaughter Veronika.

Fighters on the two warring sides, entrenched in positions about 500 feet apart, fire at each other nightly and sometimes daily. Civilian casualties are still common: in July this year, three local youths aged 3, 14, and 19 were injured by shrapnel.

We lived all our lives next to Donetsk… And now I have to treat them as enemies?

The war, which grew from a Russia-fomented uprising against a new government installed in Kiev in early 2014 after months of unrest, is often presented as a struggle between Ukraine’s Russified east and European-leaning west; between Russian and Ukrainian states, languages and histories. But here in the bakery, Yelena speaks Russian to Olya, and Olya speaks Ukrainian to Yelena. They’ve done so from kindergarten, through school and work in the bread factory; they are godmothers to each other’s children and life-long friends. Olya is red-cheeked and kindly and turns everything into a joke. Yelena has beautiful, sad blue eyes and a sometimes sharp manner, a protective wall that comes up when talk turns to the last three years’ divisions and destructions.

“We lived all our lives next to Donetsk,” she says, in an unguarded moment.

“Half of Mariinka went to work in Donetsk, and half my workers in the bread factory were from Donetsk. And now I have to treat them as enemies?”

The bakery staff don’t want to give their last names. While the town is full of Ukrainian soldiers and security services, almost everyone in Mariinka has family living or working on the other side. Bakery worker Antonina’s daughter lives in Donetsk. Oleg Tkachenko, the pastor who nominally owns the bakery, was forced to leave nearby Slovyansk in 2014 after separatists occupied the Dobra Vest church building and murdered another protestant pastor (he returned after the town was retaken by government forces in July 2014). One of Yelena’s neighbors has three sons fighting for the DNR.

“How many families have broken up because of it: who’s for Russia, who’s for Ukraine?” says Antonina. “I know ten families in Mariinka that broke up because of it.”

“We’re just people, we’re not separatists,” Yelena adds. “And all our guys just want to come home. The ones here and the ones over there, they all just want to go home.”

Before 2014, Mariinka had over 9,600 inhabitants, shops and banks, a dairy, frozen food and animal feed producers, a home for children whose parents cannot care for them, and the bread factory, which turned out 2000 loaves a day. But the 2014 battle that destroyed the factory damaged practically all industry and infrastructure, as well as stopping the busy daily commute into Donetsk. The gas supply that provided heating is still cut off, the water filtration plant inoperative. Local factories and institutions remain shuttered and ruined. The children’s home and adjacent wrecked bread factory are out of bounds, occupied by the Ukrainian army.

The social bakery produces around 1500 loaves weekly and employs eight people: bakers, an administrator, and a driver. Two schools, serving 300 pupils altogether, a kindergarten, a clinic and the military-civilian administration provide a few more workplaces. But the vast majority of Mariinka’s remaining 7000 inhabitants live entirely on humanitarian aid. Every non-ruined public building is a registration or distribution point for winter fuel, clean water, roofing material and window glass, living allowances, food parcels, diapers, medicines, and second-hand clothes.

Earlier today at the bakery shop, where Ukrainian soldiers and international humanitarian aid workers loiter drinking cheap instant coffee, every other local who comes in asks if this is the place for free potatoes. “For a week they’ve been asking if this is where to register for potatoes,” says a mildly exasperated worker. “We’re not another free-loading point.”

Pastor Tkachenko, a former successful entrepreneur, says the bakery’s aim to provide work along with affordable bread is to counter what he calls “free meal-ticket syndrome.” “It’s psychologically traumatic for basic human dignity,” he says. “People find it hard to adapt afterwards once they get used to all this aid; like a person lying down all the time who won’t move will end up with atrophied muscles.”

Work is, indeed, psychologically as well as economically vital to many in Mariinka, brought up on their industrial region’s ingrained pride in back-breaking toil. The Mariinka museum collection (bombed and looted in 2014, now under reconstruction) includes medals of thirty-six local ‘heroes of Soviet labor’.

“All we needed, all our lives, was peace and work and health,” Olya says at the bakery. “Our people don’t need anything else.”

The bakery, however, has already had to cut its positions from an initial 13. There’s rent as well as salaries to pay, not to mention the roof to fix. Tkachenko mentions plans for five more frontline bakeries, a chicken farm, and a service teaching business skills. But it’s hard to imagine anyone wanting to invest in towns where no one has a steady income, that are shelled constantly, and are under partly martial law.

Dobra Vest and its network of affiliated churches has been at the forefront of humanitarian work in war-affected areas since summer 2014, ahead of the international aid agencies whose posters now adorn pretty much everything in Mariinka. Church members transported bread from Slovyansk before the idea arose to start the bakery in Mariinka and save on transportation costs. The church contacted Yelena and asked her to run it.

Yelena had moved to Russia to live with her son and daughter-in-law, who had left Mariinka in 2014. “What else could I do? I had nothing to live for,” she tells me. “For a year I sat in the house with nothing, not a penny.”

Her son Maksim also had nothing left in Mariinka. Looking for a video of the bombed factory on her tablet to show me, instead Yelena finds videos of her son’s wedding in summer 2013. It shows a white stretch limo outside the bride’s apartment building; Yelena looking lovely and much younger—“That’s me before the war; yes, I was beautiful then,” she says dispassionately—and Olya, in the traditional role of matchmaker, bantering with the groom in raucous and joyous Ukrainian. It’s like a video from another world. No one lives in that apartment building anymore; it’s in the area by the children’s home and bread factory. The house Yelena’s son bought and furnished on credit in 2014 is also right next to the bread factory. He and his wife never had a chance to live in it. Instead “soldiers stole everything,” says his sister, Viktoria. She says these soldiers are now on trial for looting, after they were caught on CCTV driving her brother’s car.

Once the church gained permission from the Ukrainian army, Yelena returned to salvage equipment from the factory in autumn 2015. She found that all the engines had been taken out of the machinery. “Who by? Who stood there took them,” she says. “Everything was smashed and dismantled. They took what they wanted and left what they didn’t just lying there. Hardly anything was left.”

The bakery opened in 2016 with start-up funding from the Eurasia Foundation and after Czech volunteers found a firm to donate 22 tons of flour, and a transport company to drive it 1200 miles from the Czech Republic. The process took four months, including a month’s delay in Kyiv while officials demanded extra paperwork to prove the cargo was humanitarian aid. It might have been more economical to raise money to buy flour in Ukraine, volunteer Michal Kislicki acknowledges. But bakery workers say the flour was much better quality than the local ingredients they use now.

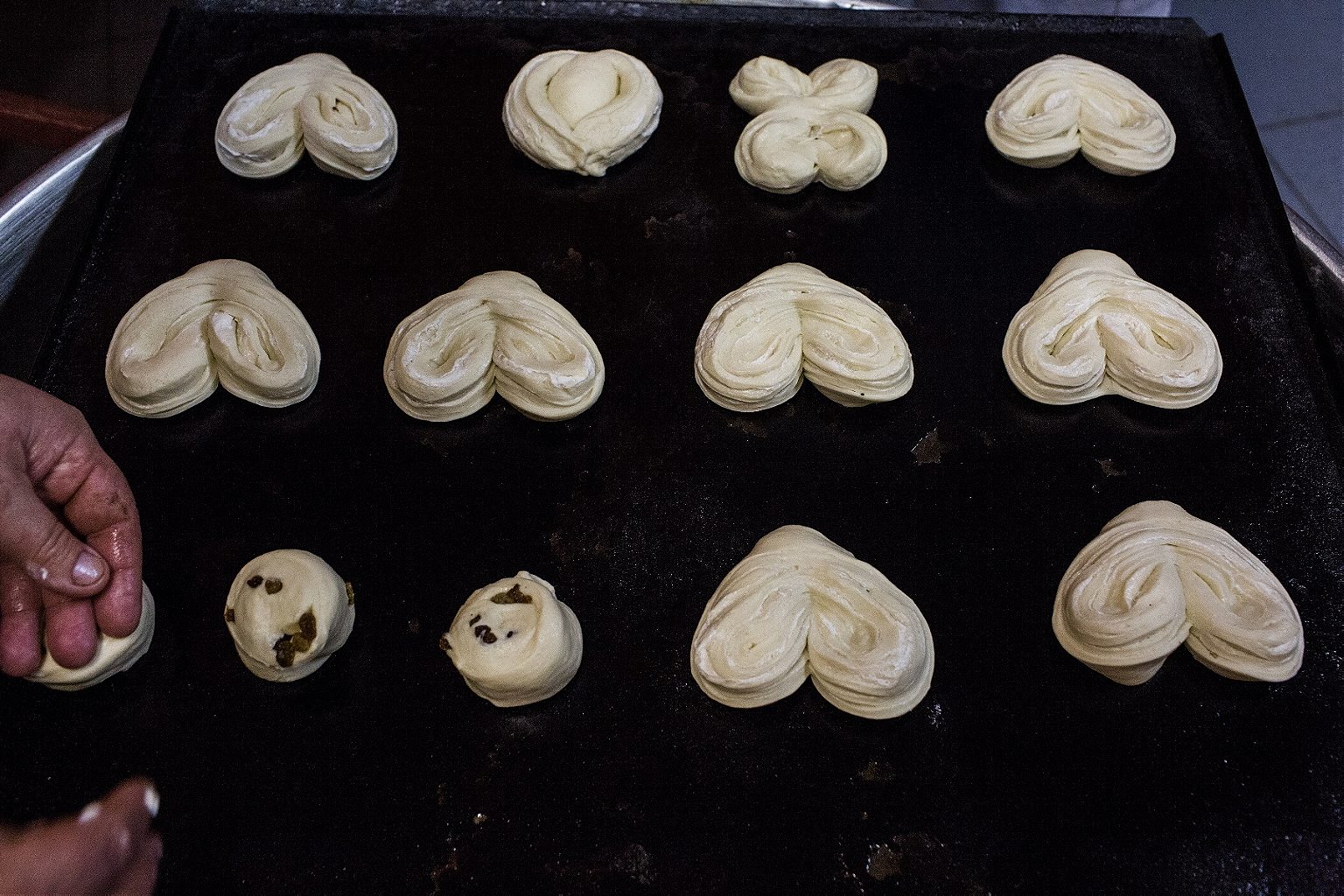

The bakery’s ingredients are simple and cheap, as supply options are limited (there’s nowhere to get fresh yeast, for example). Sweet biscuits and buns are flavored with raisins, cheese curds, jam, and poppy seed paste; pizzas feature mayonnaise, sausage, and tomato ketchup. For parties and weddings the bakery makes a layered cream cake called Napoleon, and Yelena’s speciality is korovai: round loaves decorated with intricate pastry leaves and flowers. On her tablet, Lena’s photos are evenly divided between family snaps and pictures of korovai she’s made.

Among the relics salvaged from the defunct factory is her hand-written recipe book. “It was on the floor. Everything was all broken up, and I got my courage together and collected it,” she says, showing me a recipe that includes 18 kilograms of sugar and 78 eggs. “Not to use—I know [the recipes] by heart, but as a memory.”

Today she’s making Napoleon cake for a party, and biscuits she’s christened ‘Yelena.’ “I made them up myself. We don’t have so many options; we make what we can from the ingredients they give us,” she says. “We have to invent things that are cheap but still tasty.”

The paucity of ingredients doesn’t hinder Yelena’s artistry. Outside, there are shells falling under stars that locals never see anymore. Inside, her buns this evening take the form of stars and flowers, hearts and doves. With some dough left over, she urges the photographer and I to put away camera and notebook, and turn our hands to the peaceful art of baking.

And to celebrating. After work is finished and our less-than-professional attempts at fancy buns are cooling, Yelena’s salvaged cup comes out for use as the women spread the table with beef stew and pickles, a generous off-cut of Napoleon cake, and a plastic bottle of samogon—home-made spirits—of a peculiar brown color.

The cake is delicious. The first toast is za mir—for peace—a traditional toast that used to be just something people said. No one in Mariinka three years ago would have dreamed the wish might ever become real and urgent. “And now we drink and drink for peace, but for some reason it never actually happens,” Olya jokes as we clink cups.

I ask what the home-made spirits are made from. “Sweets we collected from the cemetery, after Memorial Day,” Olya replies.

I think this must be a joke, too. It’s a strongly-observed Orthodox tradition throughout Ukraine and Russia, to place sweets and biscuits on family graves on Memorial Day each spring.

It’s not a joke. “People brought sweets in memory, and then we took the sweets to remember them by drinking.”

Mariinka cemetery, shaded by birch trees, is on the eastern edge of town, near Yelena and Olya’s homes and the frontline. The gravestones are scarred with shrapnel and bullet holes; burying and remembering the dead has become a hazardous undertaking. There could hardly, I think, be a more fitting drink than this, for an impromptu celebration of Mariinka’s extraordinary resilience, or for Yelena’s last bittersweet toast.

“Remember, and tell the world, that we’re just ordinary people,” she asks us. “Let’s drink that you’ll just come on an ordinary visit next time, and we’ll sit out celebrating in the street until dawn, and there will be no shooting anymore.”